It doesn’t seem right that most of the industry uses a template built on three layers which are each mostly wrong and not strongly supported by marketing science.

The sales funnel is nearly a hundred years old, but despite frequent reports of its death and surprisingly little evidence that it reflects how advertising actually works, it’s never been more alive. The cockroach of marketing concepts, it just seems to keep going and going, adapting to the environment it finds itself in.

This is not one of those ‘X is dead! Long live Y!’ articles deploying the ‘kill and switch’ tactic to launch a totally new thing like, for example, The Roach Rhombus. But the sales funnel needs to be adapted to today’s media environment, to fit more of the actual evidence from marketing science on how advertising works, so maybe marketing’s workhorse can keep going a few decades more.

The origin story

The now ubiquitous sales funnel started out as the linear and hierarchical ‘AIDA’ model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action) which first gained traction in the personal, door-to-door sales era of the late 19th century as a way to teach salespeople how to push buyers towards a sale in a single conversation.

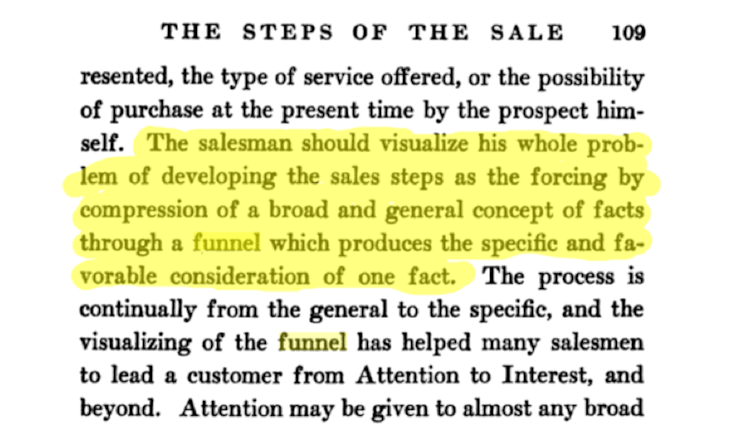

It was in 1924 that a book called ‘Bond Salesmanship’ by William Townsend first overlaid the funnel metaphor on top of the AIDA model, again as a way to push people towards a sale, but presumably this time in the context of the then-new telephone network. So its roots are as a sales aid for salespeople in the direct sales business.

Note in the extract above that originally the metaphor was more about facts being forced down the funnel than people, as in most modern interpretations. And it was originally about leading people towards a sale in a single engagement, whereas today we assume multiple phases over longer time scales, with different audiences and across different platforms.

It’s become less about individuals being taken on a journey and more about nudging large pools of different people forward stage by stage.

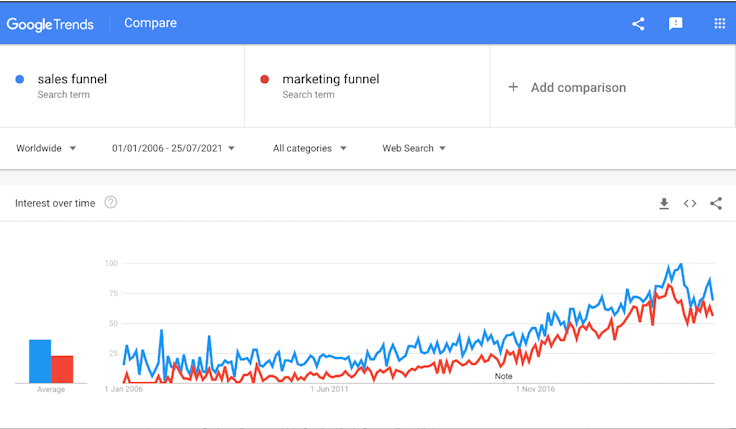

It then seems to have remained in relatively low level use for the rest of the 20th century, only becoming as omnipresent as it is today over the last decade or so.

Recent rise

A Google image search for ‘sales funnel’ instantly shows you just how prevalent it’s become. A sure sign of how useful people find it and that it’s not going anywhere anytime soon.

It’s easy to assume it’s been in constant use throughout its century of existence, but its current popularity appears to be relatively recent. During a recent conversation I had with Les Binet, he said he first became aware of the funnel in the mid-1990s in a Volkswagen strategy presentation, and that it was so little known then that the planner was assumed to have invented it.

Other conversations with people working in adland around that time suggest the funnel’s use started to ramp up in the 2000s and 2010s. So what caused its rise? My theory is that it was the growth of the adtech platforms, which needed an intuitive and simple framework to help explain how digital advertising works.

The funnel is now the menu used by the platforms to sell us their wares, helping them to explain the roles their ad formats play along the customer journey. It’s become the go-to tool for digital marketing training courses (including ours at Jellyfish) to organise and simplify the vast and ever-expanding complexity of the digital marketing universe. Media agencies use it to organise media proposals. Creative agencies use it to organise the assets they want to make.

So the funnel is, essentially, a sales tool. It is not a customer, data or science-led framework. In fact, as I’ll show, it is actually a surprisingly inaccurate model of how advertising actually works.

Who’d have thought a concept invented to teach salespeople in the late 19th and early 20th centuries would be even more powerful as a tool to help digital advertising people sell to each other in the 21st?

Common criticisms explained

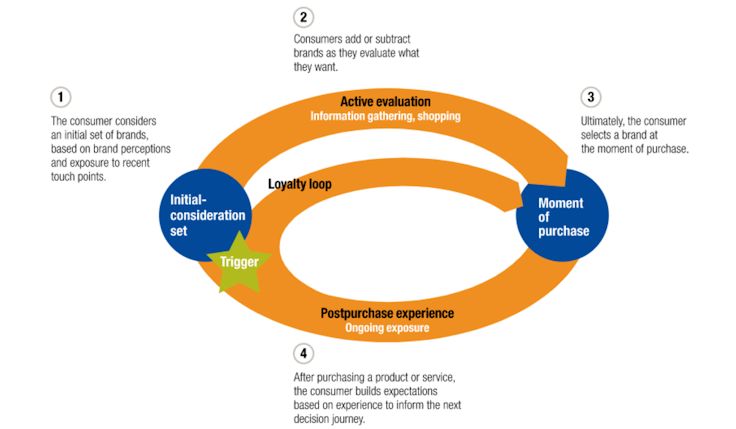

There are lots of common criticisms you can throw at the standard funnel. To start, it doesn’t encompass post-purchase or loyalty.

This is usually easily fixed by adding a couple of stages, such as loyalty and advocacy, and a loop back to earlier stages. McKinsey’s loyalty loop fixed this (illustrated below), but in doing so created a sort of Kafkaesque nightmare, where everyone is permanently considering, evaluating, purchasing or repurchasing, and ignoring the fact that in the real world people are mostly passively filtering out any kind of brand or communications most of the time.

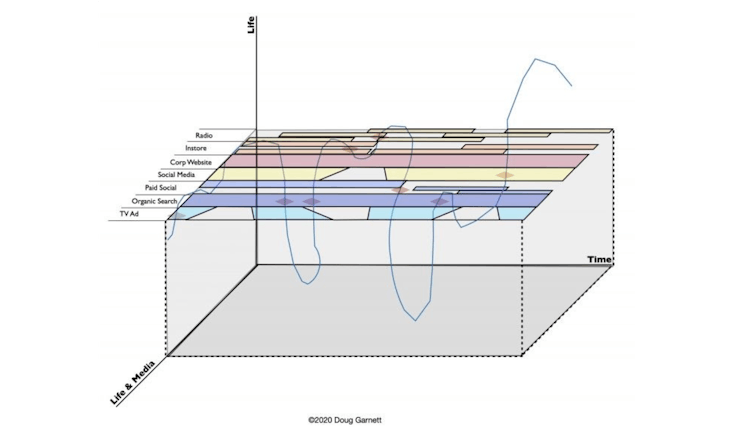

Another criticism is that funnels are too linear – that in the real world, people tend to meander around, occasionally and randomly bumping into different touchpoints on their entirely unpredictable and personal journey in time towards a sale. I love this visualisation of that chaos in Doug Garnett’s critique of a related concept, the customer journey map.

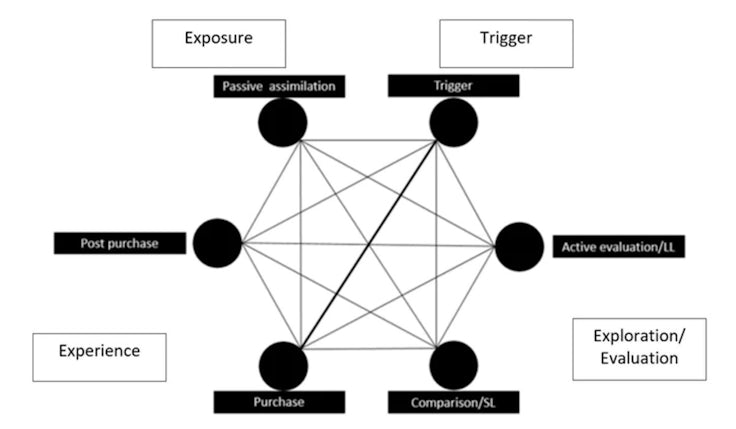

This kind of non-linear pinballing effect is touched on in James Hankins’ recent hexagon model. It’s a brilliant bit of theory, which (rare for these models) acknowledges that people start out passively, subconsciously assimilating stuff about brands, are triggered in some way, and then go on a journey which can vary in time, stages, and linearity.

Importantly it also acknowledges that this journey will vary from brand to brand and individual to individual.

In practice you’d need to identify what your core journey is for your brand, and for each stage work out what the role of communications is, and what the messaging and channels would be at each stage.

In other words, you’d end up creating your own bespoke funnel. It’s possible this model may require a little too much personalisation for most marketing people to work with.

Problems with ‘Awareness→Consideration→Conversion’

Most versions of the standard funnel are built around three basic layers – awareness, consideration and conversion. Three concepts that are all sort of wrong, but in different ways.

Few would argue with the need to make a large number of people aware of your brand. But its inclusion at the top of the funnel is a bit blunt and can lead to lazy thinking. The standard funnel almost never encompasses a concept that’s arguably more important: mental availability, or the chance of your brand coming to a buyer’s mind at key decision-making or buying moments.

Mental availability encompasses awareness, but is really a composite of spontaneous awareness, salience, distinctiveness, associations with category cues, being noticed and remembered. It rules over everything. People being aware of your brand obviously isn’t enough; people remembering it for relevant things at critical decision-making moments is what you need.

So, bluntly laying some ‘awareness’ activity over the top of your communications plan just isn’t going to cut it.‘Funnel juggling’ is the answer to marketing effectiveness

Meanwhile, almost all funnels include at their heart a period of rational, system 2 evaluation, which is usually labelled ‘consideration’. Most funnels skew somewhat to a more rational view of the world, rather than one where people’s decisions are subconscious, emotionally-driven, even irrational.

So today’s sales funnel is heavily influenced by a school of advertising thought, dominant through the early-to-mid 20th century and later adopted by most of the digital platforms, that advertising must persuade people with facts in order to get them to actively appraise and consider a product or service.

What we now know about the brain suggests this is usually not how buying decisions work. This type of evaluation is more common in low frequency, high value categories where people may want to spend more time researching options. But even then their final decisions will be primarily ‘emotional’ or subconscious.

In fact, the concept of brand consideration often doesn’t actually stand up to much scrutiny or data analysis. One major financial services client of mine, which has more analytical resources than any other company I’ve ever worked with, couldn’t find any real evidence for a causal, chronological link between brand consideration and customer acquisition.

The sales funnel needs to be adapted to today’s media environment, to fit more of the actual evidence from marketing science on how advertising works.

Its analysis identified three key metrics that mattered for its brands: 1) spontaneous ad awareness, 2) relevant brand associations, leading to 3) conversion.

It identified two roles for communications: a) simultaneously building mental availability & creating brand associations and b) triggering those associations closer to purchase. A philosophy closer to Byron Sharp’s thinking than the usual funnel.

And conversion too has issues as a label, echoing the ‘strong force’ theory of advertising, when advertising is usually only a weak force on people’s behaviour. The average clickthrough rate on digital display ads being approximately 0.07% is just one small piece of modern evidence for this, so naming a whole layer of a funnel ‘conversion’ when 99.03% of the time it’s playing some other role (e.g. refreshing brand memories) is probably over-playing advertising’s hand.

Bringing this all together

I like the funnel’s flexibility and utility. Its shape reflects the need to target broadly, to cast the net wide for prospects, to build the brand with as many category buyers as possible, creating mental availability with them, so that at the point at which they fall into the market, whether today, tomorrow or in the future, it has a greater chance of being chosen by them.

The tapering suggests deploying more targeted means to refresh mental availability and to trigger sales more directly when a smaller proportion of prospects fall into the market.

This mirrors Les Binet’s own beautifully precise articulation of how advertising really works (pictured below), which has a two-tiered funnel hidden within it: “broad reach ads that people find interesting & enjoyable and targeted activation that they find relevant and useful”. Plainly forcing people through a process or journey isn’t possible – mostly people will do things at their own speed and volition. Nudging people is more realistic.

And the unthinking application of the funnel can lead to people planning campaigns on automatic pilot, an acceptance that ‘awareness’ work can be separate, that ‘consideration’ work is essential, and that ‘conversion’ activity could be from a completely different planet.

It can lead to overly layered and fragmented campaigns with budgets being spread too thinly across multiple platforms and formats, rather than being concentrated on activity that will actually get your audience’s neural circuitry firing and creating brand memories.

And it doesn’t seem right that most of the industry uses a template built on three layers which are each kind of wrong and not strongly supported by marketing science. Awareness is insufficient as a descriptor. Consideration is not true for most people’s purchases. Conversion suggests advertising is a strong force on people’s behaviour.

The language of ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ funnel can also reinforce the value-destroying division between ‘brand’ and ‘performance’.

Some people seem to think the upper funnel is the only place where brand-building can happen, or worse, the only place where ‘creativity’ is allowed. Which can lead to people assuming that these two things are luxuries, optional extras that you only need to deploy if you’ve got the money.

Similarly, people think that ‘performance’ only happens at the bottom, when all good marketing communication should be seen as driving performance.Mark Ritson: If you think the sales funnel is dead, you’ve mistaken tactics for strategy

The standard funnel also doesn’t tend to emphasize a key role played by much digital marketing today. Not its role in helping brands to come to mind more easily, but in helping brands that have already come to mind to be found more easily. A role less akin to driving mental availability, and more akin to helping aid physical and digital availability.

Econometrician Grace Kite puts it like this: “It’s the role of online ads as signposts…this task is the online equivalent of the name above the high street front door, the lights that stay on inside, the shelf-space and even the entry in the Yellow Pages. The task is to help people who are already on their way to a website arrive safely.”

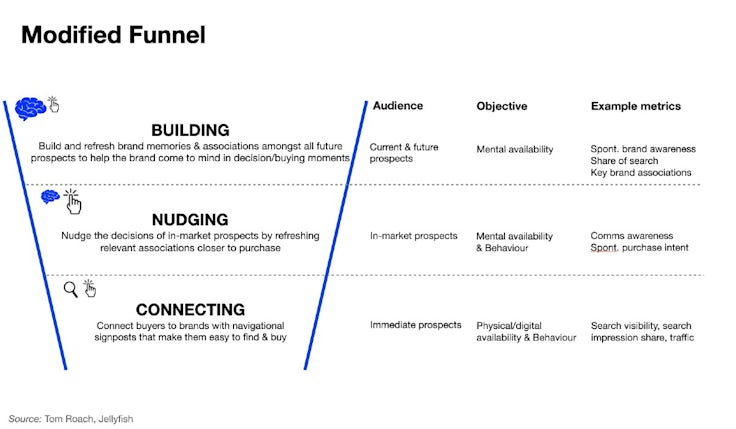

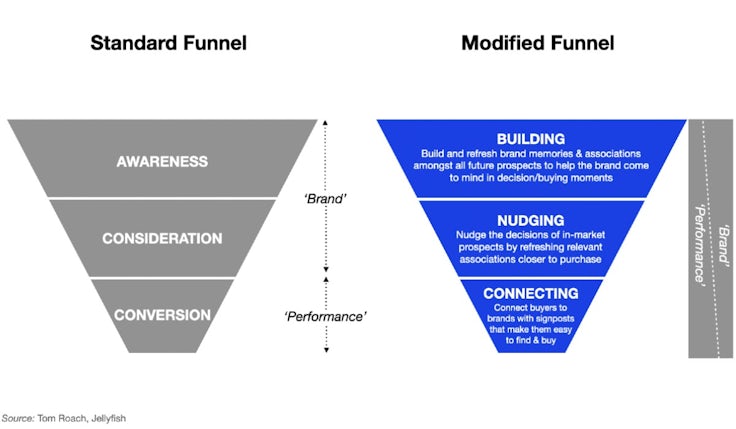

So rather than invent a totally new thing, here are some suggestions of simple modifications to the funnel to keep it up to date and in line with more of the evidence about how advertising works:

- Where building mental availability, not just awareness, is the basic role for advertising.

- Where everything is seen as contributing to brand-building and performance.

- Where advertising’s ‘emotional’ role is primary but not separate from any ‘rational’ role.

- Where an evaluation stage could be added if necessary but isn’t assumed to be needed.

- Where nudging brand memories is used as a way to trigger short-term sales.

- Where the connecting role of paid search and SEO in helping make brands be easy to find is highlighted as an important and distinct role for communication today.

The modified funnel would look something like this:

As they say, all models are wrong and some are useful. But perhaps this simple adaptation of the standard funnel could be a little less wrong and a little more useful.

But whichever version of the funnel you use, don’t allow any version of it to let you do your planning on auto-pilot. Determine the actual path to purchase for your brand, the best role for communications at each stage, the metrics that matter at each, deploy the best media mix and make the very best creative you can to shift them.

The sales funnel has been in use for nearly a hundred years by adapting to the media environment of the day. If we continue to adapt it to what marketing science tells us about how advertising works, perhaps it could be in use for the next hundred.

The sales funnel is nearly a hundred years old, but despite frequent reports of its death and surprisingly little evidence that it reflects how advertising actually works, it’s never been more alive. The cockroach of marketing concepts, it just seems to keep going and going, adapting to the environment it finds itself in.

The sales funnel is nearly a hundred years old, but despite frequent reports of its death and surprisingly little evidence that it reflects how advertising actually works, it’s never been more alive. The cockroach of marketing concepts, it just seems to keep going and going, adapting to the environment it finds itself in. It’s easy to assume it’s been in constant use throughout its century of existence, but its current popularity appears to be relatively recent. During a recent conversation I had with Les Binet, he said he first became aware of the funnel in the mid-1990s in a Volkswagen strategy presentation, and that it was so little known then that the planner was assumed to have invented it.

It’s easy to assume it’s been in constant use throughout its century of existence, but its current popularity appears to be relatively recent. During a recent conversation I had with Les Binet, he said he first became aware of the funnel in the mid-1990s in a Volkswagen strategy presentation, and that it was so little known then that the planner was assumed to have invented it. The funnel is now the menu used by the platforms to sell us their wares, helping them to explain the roles their ad formats play along the customer journey. It’s become the go-to tool for digital marketing training courses (including ours at Jellyfish) to organise and simplify the vast and ever-expanding complexity of the digital marketing universe. Media agencies use it to organise media proposals. Creative agencies use it to organise the assets they want to make.

The funnel is now the menu used by the platforms to sell us their wares, helping them to explain the roles their ad formats play along the customer journey. It’s become the go-to tool for digital marketing training courses (including ours at Jellyfish) to organise and simplify the vast and ever-expanding complexity of the digital marketing universe. Media agencies use it to organise media proposals. Creative agencies use it to organise the assets they want to make. As they say, all models are wrong and some are useful. But perhaps this simple adaptation of the standard funnel could be a little less wrong and a little more useful.

As they say, all models are wrong and some are useful. But perhaps this simple adaptation of the standard funnel could be a little less wrong and a little more useful.