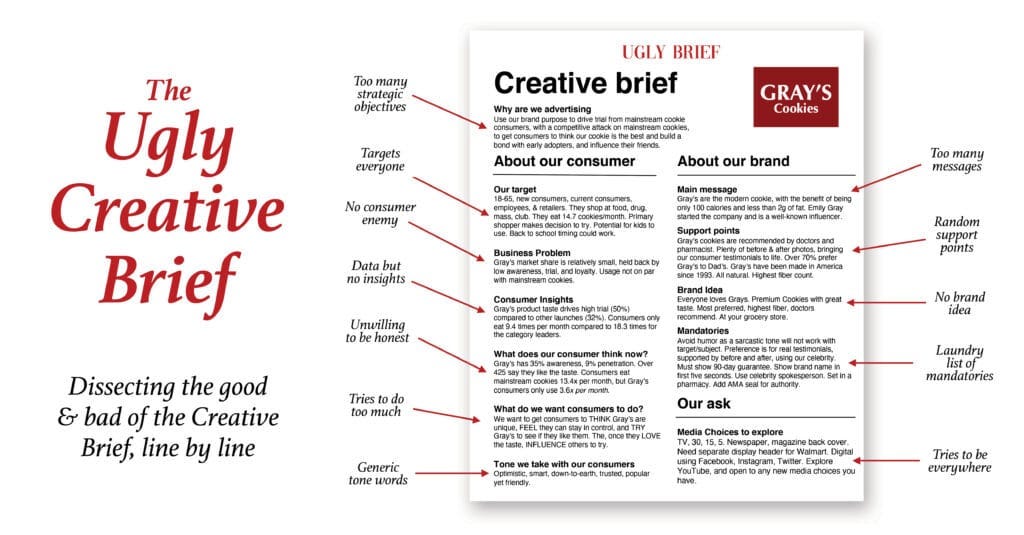

Dissecting the good and bad of the creative brief, line by line

Before writing a creative brief, make sure you have done your homework on developing a winning brand communications strategy that combines the work of your brand positioning, brand idea, and the brand plan. The briefing stage plays a crucial role as the bridge between your smart strategy and your brilliant execution.

I believe brand leaders should control the strategy, yet give more freedom on execution. Too many marketers have this backward. They give up too much freedom on strategy then try to control the creative outcome of the execution.

Make the tough decisions to narrow the brief down to:

- One strategic objective

- One tightly defined consumer target

- One desired consumer response

- One main message

- Two reasons to believe.

I meet resistance when I show people that list. You should see the resistance that your 8-page brief will meet.

To illustrate, click on the ugly creative brief to zoom in.

Our good creative brief

I will dissect the creative brief, with a line-by-line review to demonstrate examples of smart and bad creative briefs. Moreover, I will use some real case studies of bad briefs I have seen over the years to show you what not to do. I will use some of our principles I have talked about to show you a smarter brief.

While each line in the brief has a role to play, the brief should have a natural flow. Similar to how we describe your brand plan as flowing like an orchestra arrangement, when any line of the creative brief feels like it is playing the wrong note, it will stand out like a complete misfit.

To illustrate, click on the brief to zoom in for details.

1. Why are we advertising?

A bad brief has an unfocused objective:

- Drive trial of Gray’s Cookies, steal market share from mainstream competitors while getting current users to use Gray’s more often.

A smart brief has a focused objective:

- Drive trial of Gray’s Cookies, using the positioning of “The good tasting healthy cookie.”

Smart briefs start with one very clear objective, while bad briefs try to accomplish too many things at once.

If you get this line wrong, it can destroy the entire brief. With the example above, the smart brief narrows the decision to one objective (drive trial). A clear objective helps steer the direction for the rest of the brief. The bad brief makes the mistake of trying to do two things at once.

I see too many brands put “drive penetration and usage frequency” at the top of the brief. It is the sign of a lazy mind. Do you realize how different these two strategies are? Can you see how much you will drain your resources when you try to do both with the same ad?

These two strategies have two separate targets, two different brand messages, and potentially two different media plans. Your agency will divide the brief in half, and come back with one ad to drive penetration and another to drive usage frequency. As a result, you will pick your brand strategy based on which ad you like best.

One objective

If your brand has an issue with both penetration and usage, I recommend you write two separate creative briefs, with two independent projects, budgets, and media plans. From a brand plan viewpoint, I would also recommend you stagger these two strategies into different fiscal years to ensure you are not just dividing your limited resources and doing a poor job with both strategies.

Do you want to get more people to eat, or the same amount of people to eat more? Pick one.

Penetration vs. usage frequency

A penetration strategy gets someone new with minimal experience with your brand to consider dropping their current brand to try you once and see if they will like your brand. That will take a lot of hard work.

A usage frequency strategy gets someone already familiar with your brand, and you have to convince them to change their behavior about your brand. They will either have to change their current life routine or substitute your brand into a higher share of occasions.

Pick one strategy, not two

2. Who are we talking to?

A bad brief has an unfocused target:

- 18–65 years old, including current consumers, new consumers, and employees. They shop at grocery, drug, and mass retailers. They like cookies and eat 14.7 cookies a month.

A smart brief has a focused and well-defined target bulls-eye:

- “Proactive Preventers.” Suburban working moms, 35–40 who are willing to do whatever it takes to stay healthy. They run, work out, and eat right. For them, food is a stress-reliever and an escape. Even for people who watch what they eat, there is still guilt when they cheat.

One of the most significant correlations with brand success is for consumers to playback and feel, “This brand is for me.” You can only achieve that by speaking directly with a precise, tight bullseye consumer target.

A smart brief uses a combination of demographics, behaviors, and attitudes, and links how a cookie could fit into other parts of their healthy lifestyle. These details paint a full picture of who we are talking to. In the bad, unfocused creative brief above, the target is pretty much everyone, so it will be hard for anyone to feel the advertising is speaking directly to them.

3. What’s the consumer enemy we are fighting?

A bad brief has the business problem as the lead:

- Gray’s market share is still relatively small, held back by low awareness and trial. Product usage is not on par with the category.

A smart brief has a clearly stated consumer problem:

- Consumers struggle to fight off the temptation of cookies and feel guilty when they cheat.

The brief should reflect a consumer problem, not a business problem related to how consumers buy your brand. Think back to the target market chapter and use your consumers’ pain point or enemy, which torments them every day. Think of how your brand will battle that enemy on behalf of your consumers.

In the example of a smart brief, the consumer’s enemies are “temptation and guilt.” When you put an emotional enemy in your brief, it allows the creative process to get into the emotional space right away. That is much more powerful than a functional problem such as losing weight or reducing calories.

In the bad brief example above, the focus on function rather than emotion is a classic flaw of leading with a business-driven problem that talks about a brand’s problem with consumers.

4. Consumer insights

A bad brief has data over insights:

- Gray’s product taste drives high trial (50%) compared to other new launches (32%). Consumers use Gray’s 9.8 times per month compared to the category leader at 18.3 times per month.

A smart brief has deep, rich insights:

- Once consumers cheat on their diet, it puts their whole willpower at risk. They keep cheating. “Once I give in to a cookie, I can’t stop myself. They just taste too good. It puts my diet at risk of collapsing. I feel guilty. However, I can’t stop myself from cheating again.”

The smart brief above really goes deep to gain an understanding and build a story through the voice of the consumer. It captures their inner thoughts, uses their own word choices, and expresses their feelings.

In the bad brief, there are no real insights. It is just a bunch of data points, without any depth of explanation or story. It will be hard for the creative team to write an engaging story with stats.

5. What does our consumer think now?

A bad brief provides data only, without a well-drawn conclusion:

- Gray’s only has 35% awareness and 9% penetration. Over 42% of consumers say they like the taste. However, consumers only eat Gray’s 3.6x per month.

A smart brief defines where consumers currently are with the brand:

- Gray’s Cookies have achieved a small growing base of brand fans, but most consumers remain unfamiliar and have yet to try Gray’s. Those who love Gray’s, describe it as “equally good on health and taste.”

You can use the brand love curve from the consumer strategy chapter to capture how consumers feel about your brand. Use the analytics from brand funnel analysis, the voice of consumer (VOC), market share data, loyalty data, and net promoter scores to determine where your brand sits on the curve.

The bad brief above just throws out random statistics; it fails to turn the data into stories that form a meaningful analysis. The smart brief draws an honest conclusion that your brand is at the unfamiliar/indifferent stage for most consumers. The statement also sheds light on what the few who love the brand say about it, suggesting what might motivate others.

Click on the diagram to zoom in

6. What do we want consumers to do?

A bad brief tries to trigger too many responses:

- We want consumers to THINK Gray’s Cookies are unique, to get consumers to FEEL they can stay in control, and then we want them to TRY Gray’s and see if they like them.

A smart brief focuses on the desired response that comes from the strategic objective:

- Get consumers to TRY Gray’s and believe the great taste will win them over.

The best advertising can only get the consumer to do one thing at a time, so you should focus your desired response to get consumers to see, think, do, feel, or influence others. Decide on what you want the desired response to be before you decide on the stimulus, which is the next question of the brief.

The bad brief above sets up an unrealistic attempt to get consumers to think, feel, and try — and all in one ad. The smart brief narrows the focus to drive trial, which aligns with the strategic objective of the brand plan.

Too many marketers already know what they want to say before they even know the response they want from their consumers. Start with the desired response, which comes from your brand plan, and only then can you decide what to say to achieve that response.

7. Tone we will take with our consumers

A bad brief uses clichés that are all over the emotional map:

- Optimistic, smart, down-to-earth, trusted, popular, and yet friendly.

A smart brief focuses on the emotional zones your brand is trying to win:

- A safe choice to stay in control. An honest and down-to-earth option.

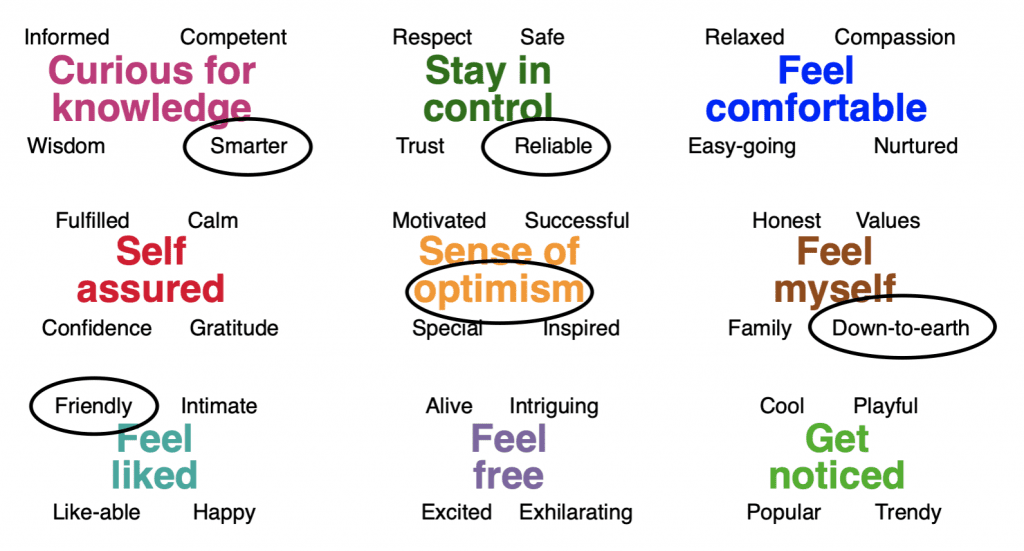

With Gray’s Cookies, the two emotional zones the brand positioning focuses on “stay in control” and “I feel good about myself.” The related support words, including safe, honest, and down-to-earth, can help define the ideal emotional tone and manner of your brand.

The bad brief is all over the map with emotions. It seems half the briefs I see contain “smart, trusted, reliable and friendly.” It has almost become clichés without thought.

Using our emotional zones from the brand positioning process, you will see those words fall into five distinct emotional zones. These words would make your brand appear schizophrenic in tone.

Read our story on how emotional advertising tightens the bond and grows your brand.

8. What should we tell consumers? (Main message)

A bad brief tries to communicate too many things at once:

- Gray’s Cookies are the perfect modern cookie, only 100 calories and less than 2g of fat. For those looking to lose weight, the American Dietitian’s recommend adding Gray’s to your diet. You can find Gray’s at all leading grocery stores.

A smart brief focuses on one main message, bringing the consumer benefit to life:

- Try Gray’s Cookies, the great tasting cookie without any guilt.

The smart brief above narrows down to one thing, the big idea of “great taste without the guilt.”

The bad brief has a laundry list of seven unrelated messages. Most are just product features, instead of a primary consumer benefit. It is a marketing myth to believe that if you tell the consumer a lot of things, at least they will hear something. The truth is that if tell consumers too many messages, they will just shut you out and not listen to anything you say.

9. Why should consumers believe us?

A bad brief lists random claims about your brand:

- Gray’s Cookies are the cookies recommended by doctors and pharmacists. Plenty of before and after photos, and consumer comments. Over 70% of consumers prefer Gray’s to Dad’s. Gray’s cookies have been made in America since 1963, containing all natural ingredients. No one beats Gray’s for fiber content.

A smart brief uses the support points to close off lingering gaps:

- In blind taste tests, Gray’s Cookies matched market leaders on taste, but only has 100 calories and 2g of fat. In a 12-week study, consumers using Gray’s once a night as a dessert lost 5 pounds.

Only use support points to close off any potential gaps in your logic. Listen to consumers for possible doubts they may have relative to your main message. Based on Logic 101, you can win any argument using two premise points to conclude. The same should hold true for a brand. Force yourself to use a maximum of two support points.

The smart brief above focuses on two support points, which back up your main message. The bad brief throws out random claims that have nothing to do with the main message.

10. Brand idea

A bad brief throws out random features to anyone:

- Anyone could love Gray’s Cookies, premium cookies that taste great. Over 70% of consumers prefer Gray’s to Dad’s. Gray’s cookies come from a homemade recipe. Doctors and pharmacists recommend them. You can buy them at your local grocery store.

A smart brief uses the brand idea that organizes everything we do:

- Gray’s are the best tasting yet guilt-free pleasure so you can stay in control of your health and mind.

The smart brief uses the brand idea that drives everything we do. The bad brief example above targets everyone and lists random features and claims. However, it does not contain any consumer benefits. If you only tell consumers what you do, and not what consumers get, you risk leaving it up to their interpretation.

11. Brand Assets

A bad brief throws out random features and ideas to control the creative:

- Avoid humor, as a sarcastic tone will not work with our target market. Real customer testimonials supported by before/after with our 90-day guarantee tagged on. Use our celebrity spokesperson. Increase credibility by having set in a pharmacy. Add our AMA doctor recommendation seal.

A smart brief uses distinctive creative and strategic assets to build behind:

- Story of our New England family recipe, our signature stack of beautiful cookies, “More Cookie. Less Guilt.”

The smart brief builds creative and strategic assets. Stay confident that you have written such a great brief, that you do not need to control the creative outcome.

12. Media choices

A bad brief uses too many media choices, especially early in the process:

- TV, 30-seconds, and 15-seconds. Include 5-second tag for promotions. Print includes magazine and newspaper. Need separate display headers for Walmart. Need to use Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Must be able to use video on our website and YouTube channel.

A smart brief provides a range to see what the creative looks like first:

- Main creative will be a 30-second TV ad, supported by event signage and in-store display. Want to carry the idea into digital and social media, and build a microsite.

At the briefing stage, you might have ideas around what type of media you want to use, but it is difficult to know the ideal media until you see the creative idea. At this point, provide a potential media guideline, with a lead media option and possible media choices to support.

The unfocused bad brief above offers a laundry list of media choices, which will only spread your limited resources so thin that nothing will have the desired impact you hope for. When you try to be everywhere, you might end up nowhere.

Here’s a simple way to make sure your creative team covers almost every potential media choice. Ask to see each creative idea presented through a 30-second TV script, a simple billboard, and a long-copy print ad. This process allows you to see how each creative idea plays out on almost any media option before you start to narrow down your media planning. Asking for TV, billboard, and a long-copy print for each creative idea will allow you to imagine how it might look using any of 12 potential media choices.

Mandatories

A good brief gives freedom to the creative team to explore:

- The line: “best tasting yet guilt-free pleasure” is on our packaging. 25% of the print must carry the Whole Foods logo as part of our listing agreement. Include our legal disclaimer on the taste test and 12-week study.

A smart brief has very few mandatories with none of them steering the creative outcome. Stay confident that you have written such a great brief, that you do not need to control the creative outcome. Give some creative freedom to allow your agency the opportunity to look at the best way to express and deliver your strategy. The bad brief uses mandatories to steer the creative outcome with a prescriptive list that backs the agency into a creative corner. With this bad brief, for the agency to tick off each mandatory, they will create a messy, ugly “Frankenstein” ad to try to piece everything together.